The 1st Independent Polish Parachute Brigade

(1 Samodzielna Brygada Spadochronowa)

An Entire

Family Deportation

Deportation

The entire family (apart from Wladyslaw) were deported on 13th April 1940 from Białystok to Kazakhstan, the Pavlodar Oblast, the Pavlodar region, Koriakowski prom-sol. The labour camp they were at consisted of shovelling salt into railway trucks all day long. A fellow survivor wrote here account here.

Testimony Of Stanislawa (My Wife)

This is the testimony of Stanislaw Gostik (Hostik) and related deportation/repatriation documents from Zwiazek Sybirakow here: http://www.sybiracyzg.pl/

Click the first photo to enlarge it and enter the gallery.

Testimony Of Zdzislaw (My Son)

This is the testimony of Stanislaw Gostik (Hostik) and related deportation/repatriation documents from Zwiazek Sybirakow.

Click the first photo to enlarge it and enter the gallery.

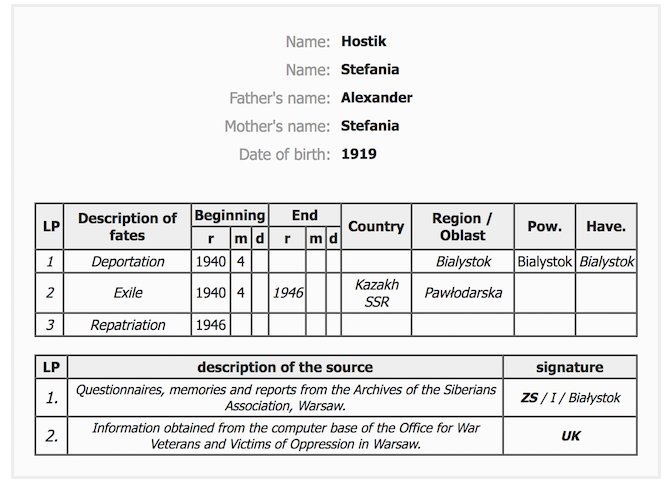

Family Records In Index Of The Repressed

The records of my sisters Regina Hostik and Stefania Hostik can be seen on the Index Of The Repressed here.

My other sister Irena Hostik and my son Zdzislaw Stanislaw Hostik are recorded on The Index Of The Repressed here. But as their names were given Russian equivalents after Russia invaded in 1939, their surnames are listed as "Gostik".

The Knock

The story as told by Stanislawa (Wladyslaw's wife), in re-created format.

It all started one night early in 1940.

The family was asleep. Just a few hours earlier I had bathed my 2 year old daughter Lucyna also my 3 year old son, Zdzislaw and put them both in their beds.

They had been very tired tonight, it had been a long day as we had been out as a family into the country. I had made a picnic and Wladyslaw had taken us all to a lovely spot in the country that we all knew well.

The children had played with their dad in the grass, playing hide and seek as well as trying to kick a ball around. He had taken them to the little river nearby where they had paddled at the waters edge. It had been such a lovely warm day.

I had prepared some food for a picnic lunch. There was kielbasa, ogorki and Wladyslaws favourite, chrzan (Horseradish) along with his other favourite grzyby (wild mushrooms from the forrest). His mother Stefania had baked us a load of bread as well and I had put in a few other foods for the kids.

What a lovely, peaceful, family day it had been for all of us.

It was now being rudely ruined. There was a loud rapid knocking at the door. It sounded like rifle butts were being hammered against the front door and there were orders being shouted to open up right now!

"Oh no, not us, please God not us!". I knew what this was. I had heard the stories and even seen this happen to some of my neighbours lately.

A Soviet officer accompanies by 2 other Soviet men stood outside. I could also see Piotr, the local communist sympathiser hanging about, looking half proud but also looking like he was up to no good.

Wladyslaw was coming out of the bedroom and walking towards the door behind me, the children too had been awoken by the rapid loud noise and Lucyna was now crying for me.

My heart was sinking. All that we held dear was about to be destroyed. I looked over the Soviet soldiers shoulder, I could see the same scene being replayed at my in-laws house. We were all in a serious situation now.

The Soviet soldier pushed past me into the house and for no no reason at all suddenly and violently smashed his rifle but into my husbands face. He fell down, yelling in pain. "Get up pig!" yelled the Soviet officer. Wladyslaw continued to moan in pain. The Soviet officer then swiftly kicked Wladyslaw with his long shiny boot. "Up! Now!" he yelled. Wladyslaw got up. The kids screamed louder.

They pushed us into the livingroom. My husband was again struck with a rifle butt and we were forced to line up against a wall, putting our hands on it, whilst the Soviets searched us for weapons.

One of the other officers then went around the house, searching. What are they searching for I wondered? The answer soon came by way of a question. "Where are your weapons?" he yelled. I replied that we had none, but he still searched until satisfied that we had none.

Whilst Wladyslaw was forcefully detained by way of a bayonet being held at his throat, I was told we had 30 minutes to pack a few things.

Quickly I packed some food, a few photos and keepsakes. I also took warm clothes for the children and Zdzislaws teddy bear and Lucyna's doll. I knew where we were going and I had to keep my children warm, fed and with something left of their innocent childhood.

We were pushed out of the house. Out in the courtyard were Stefania and Aleksander, my in-laws. Nearby was also Regina, Stefania, Aleksander and Irena all brother and sisters of my husband. "Dear God, do you see what badness is happening?" I thought? But there was no more time for thinking.

We were told to get onto the carts. They stunk of horse manure, there was not even a covering to protect us from getting out clothes dirty. But I knew where we were going, our clothes being clean was the last of my worries.

My husband, Wladyslaw was put on a different cart and taken away first, in the opposite direction. At the time I did not know it, but I would never see him again.

The snow fell lightly out the sky. It was maybe 2am in the morning, all was quiet. The wheels of the cart creaked as they went through fresh snow. Not a word was said by us. We looked at each other, sadness in our eyes, as if a death sentence had just been announced. Well, it had, I thought.

As we travelled, a few other carts also with families on them joined us in procession. A couple of local neighbours had been awoken by the noise and had come out to see what was going on. One or two of them quickly ran to us to say goodbye, tears in their eyes.

We could not speak out of sadness, intense sorrow and also the fact we had been warned by the Soviets to say nothing. I held Lucyna closer to my body and put an arm around Zdzislaw. How was I going to get the children through this?

The Railway Station

The cart pulled into the railway station. A very long train was standing there quietly. There was no noise or smoke from the engine. I knew that a few days ago some neighbours had been taken like we had, I could now hear them calling out from inside a railway carriage. Had they been here all this time, I wondered?

A carriage door was opened. It was hard to tell as there was little light but inside were maybe 50 people, squeezed together tightly, so tightly. They look worn out, black circles around their eyes, lifeless.

All the females from our family were pushed inside, whilst both Aleksanders were put in another carriage for men only. I felt life itself being squeezed out of me for so tightly did we have to squeeze together to fit in.

Lucyna needed changing and Zdzislaw was complaining he was cold and needed the toilet. This was a disaster, even as their mother I was not prepared for dealing with this.

The door was closed and locked. Silence and darkness was all around. Whispers in the carriage started up as we talked amongst ourselves quietly for fear of retribution from the Soviets.

"How long have you been here?" I asked the neighbour I recognised. She told me for 4 whole days she had been in this carriage but there were others that had been in the carriage for nearly 3 weeks. "What? 3 weeks locked in a railway carriage going nowhere?" I asked. "Yes", she replied "and we are being given a slice of bread a day and little water. We have even made a hole in the floor as a toilet because the Soviets will not allow us to use the toilets at the train station".

I was in shock. The Soviets were treating us worse than we would treat farm animals. I started crying, it was too much for me as a mother to bear this load, to see these horrors.

Stefania (Wladyslaws mother) comforted me and held Lucyna for a while as I comforted Zdzislaw. He eventually used the hole in the floor for the toilet, it was so difficult and embarrassing for him, with so many people around him and no privacy.

Through the night we heard many more arrivals being put into carriages. We called out to each other occasionally, hoping for new information, but no-one knew anything.

Through the cracks in the wood of the carriage I saw light get stronger as morning came. The engine was started and there was a lot of activity around the train we we prepared to leave.

Eventually, the train pulled away. All of us took turns to look through gaps in the wood. We could see Bialystok fading into the distance. We all secretly wondered if we would ever see it again.

In the distance I could see the steeple of Farna Parish where I had married Wladyslaw just a few years earlier. It seemed so ironic that this steeple was a memory of a place that would bring us together in marriage but would also be the last thing I saw as I separated from Wladyslaw.

Travelling To Kazakhstan

The rhythmic clicking of the train tracks did nothing to calm our nerves. We were all highly distraught, weeping, crying, calling out to God. We felt so helpless. And cold. Dreadfully cold.

The cold permeated your very bone marrow, your breath froze in the air. No matter where you put your hands for heat, or how tightly you arranged your clothes the cold got through.

I kept checking that little Lucyna and Zdzislaw were okay. Secretly I was worried for their very lives, if they would make it at all. And once we got to wherever it was the Soviets had planned for us, what then? I did not dare think of all the possibilities.

In the tightly packed railway cattle carriage there was no privacy, people defecated where they stood, even died. In our carriage alone a few people died.

One was passed out through the hole in the floor, another was flung out of the carriage when we stopped at a railway station and yet another we buried in a shallow grave on a railway siding when the engine stopped for a while.

There was no honour in this carriage, either in life and it's natural functions of the toilet, or in death. We had been reduced to existing, to savages.

For 4 weeks we travelled like this. I was worried for Lucyna, we had no facilities and being only 2 years old she needed her nappy changed, but we had nothing. I did the best I could as a mother but she came out in a horrendous rash and screamed constantly in pain. It was breaking my heart.

The little food I had been able to pack sustained us a little but there were many in the carriage who had nothing with them. A few others had managed to bring a barrel with them containing salted pork and we all shared with each other because life was our common goal and we could not make it without the help of each other.

Occasionally the train wold stop to refuel at railway stations and the carriages would be opened up. We would quickly run to suitable areas where we could have the privacy to attend to toilet needs.

I learnt to ignore the ice cold snow and experience the freedom to have a minutes privacy. Then it was a mad dash to the engine which had a tap that gave hot water, We would get some of this and try to make tea out of any leaves or similar matter that we could scavenge.

We had to keep a sharp eye out for the train leaving because if you did not the train would leave without you. Some where left behind and despite their protests the train left. What became of them I do not know. Maybe they had a better life or maybe they died, we never did find out.

Kavikowka, Kazakhstan

One day the train stopped unexpectedly. Our door was slide open and we were urged to get out. "Quickly, quickly, hurry up!" they urged us. The train carriage was high up and it was a difficult matter to get out of it, you had to carefully climb down and iron ladder.

I had Lucyna and Zdzislaw to think about but luckily the Soviet officers did not see us and we managed to get out without suffering the unexpected rifle butt in the back that some got.

Where are we? I asked the officer. Kavikowka, Pawladarska, Kazakhstan he mockingly told me. He then informed the group we would be here to do hard labour, shovelling salt in railway trucks.

I was in shock! What was supposed to happen with little Lucyna and Zdzislaw I wondered?

I asked the officer, probably because I was just so completely shocked by their expectations. "If you don't work, then you don't eat"he told us.

I fell silent. I needed time to process how evil and twisted this whole thing was.

We were forcibly marched to some buildings. These barracks were to be our accommodation, a bucket in the floor our toilet. Well, Stanislawa, I thought, it's an improvement on the railway carriage. I told myself this partly in irony and partly to try and remain positive, if not for my sake then the sake of the children and the hope of getting out alive to see my dear Wladyslaw again.

That night I slept the best sleep ever, finally able to do this lying down and not standing up as we had done on the train. Lucyna was by my side and Zdzislaw slept behind me.

Our Daily Work at Kavikowka

Content To Follow..

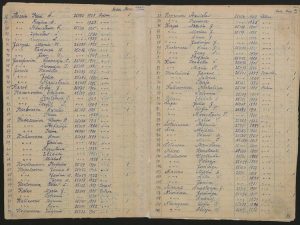

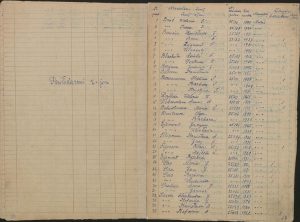

The Book of Pawladarska

When we arrived at Pawladarska our names were recorded in the "Book Of Pawladarska". This would later be in a Museum In Bialystok for my family to find in 2019.

Please Donate!

Uncover The Past - Support The Future

Please don't "grab & go"! Each year, 12,000 people visit this website to trace their Polish ancestry, uncover family stories, and connect with their roots. I believe that history should be accessible to all - but keeping this website alive since 2017 comes at a personal cost to me, 8 years @ £1000 per year (website mgt fees) has left an £8000 dent...with only £502 in total donated up to 31/01/26 😱😱😱.

Every detail you uncover and every story you piece together helps you piece family history together. Please donate if you found the existing information on this site useful, help me keep the site alive! Thanks! Jason Nellyer (Researcher & Site Owner)

PS - You'll even get a personal thank you for me for any donations. Truly valued!